Countries in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) have achieved significant levels of malaria reduction, but many still face the challenge of residual malaria. With the emerging threat of drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in the region, it is critical to work at pace to eliminate malaria and prevent it reaching Africa, where most of the world’s malaria cases are.

Malaria Consortium has been operational in the GMS region since 2003, supporting national malaria control programmes to strengthen the region’s capacity to help advance progress towards malaria elimination. This includes providing technical leadership, programmatic coordination and strengthening partnerships through the development of online training courses. A key aspect of this is through conducting effective vector control.

A brief history of malaria vector control

Since the discovery in the late 1800s that malaria is transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes, vector control has been the primary tool for combating the disease. Initially, control tools were based on larval control – spraying Paris green (copper acetoarsenite) on breeding pools, draining of ditches and marshes – and screening of windows and doors in homes. Following the Second World War, the insecticide – dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) – was introduced for mosquito control. This resulted in an extensive global spray campaign, which succeeded in shrinking the malaria-endemic map in many parts of the world, and dramatically reduced case numbers in many areas. However, insecticide resistance developed within mosquitoes, due to the large-scale spraying that had not only targeted mosquitoes but also agricultural pests.

This, together with parasite resistance to chloroquine, led the World Health Organization (WHO) in the 1960s to replace the goal of global malaria eradication with malaria control. In the 1990s, the incorporation of highly effective synthetic pyrethroids into bed nets resulted in a widespread uptake of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) globally. This resulted in major reductions in malaria cases between 2000 and 2015, when insecticide resistance and other factors once again resulted in control efforts stalling, prompting the search for new tools.

All these malaria vector control efforts depend upon effective vector surveillance. The most obvious of these surveillance needs is to monitor the insecticide resistance status of local vector populations. Many other aspects need to be monitored as well, such as determining which vector species are present in a particular area and whether they primarily bite and rest indoors or outdoors – all of which can impact upon decision-making about appropriate vector control tools.

Global progress with ITN campaigns has led to a new challenge. In earlier decades, entomologists were recognised as key members of national malaria programmess and adequate staffing and training of them was ensured. However, as these focused on distributing millions of ITNs, steady attrition of entomologists resulted through a lack of replacement of qualified staff many entomologists. Consequently, there is now a global shortage of entomological skills to underpin vector control programmes, as has been indicated in several international publications including a recent article in the Journal of Communicable Diseases.

Introducing the International Malaria Vector Surveillance for Elimination (MVSE) course

To address this shortfall of entomological surveillance skills, the Asia-Pacific Malaria Elimination Network (APMEN), through its Vector Control Working Group (VCWG) led by Malaria Consortium, has for several years engaged countries and stakeholders in vector surveillance capacity strengthening, through exchanging technical and programmatic guidance between regional malaria control programs and elimination partners in the Asia-Pacific region. One of these interventions has been organising an annual, two-week course, covering most aspects of malaria vector surveillance.

The first International Malaria Vector Surveillance for Elimination (MVSE) course was held in 2018 and hosted by the Institute of Medical Research in Kuala Lumpur, while the second was hosted by Kasetsart University in Bangkok in 2019. The COVID-19 pandemic prevented us from holding similar courses in 2020 and 2021. But this year, the third MVSE course will be held at the Mohanlal Sukhadia University in Udaipur, India. We will also be regionalising the course – inviting applications from National Malaria Control Programme staff and also research institutions from six nations in South Asia, with the intention to repeat the course in the Malay Archipelago and Melanesia Region in 2023.

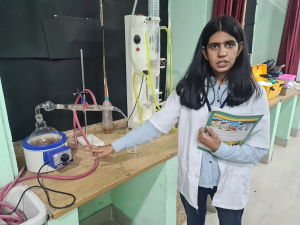

MVSE is an intensive training course, covering topics such as the development of a surveillance programme and mosquito sampling techniques, with field trips to have hands-on experience in larval and adult collections of mosquitoes, mosquito identification, insecticide susceptibility monitoring, insectary establishment and maintenance and other aspects.

To host and implement the training course this year, we are fortunate to have the support of the Laboratory of Public Health Entomology in the Department of Zoology of the Mohanlal Sukhadia University in Udaipur, India. This laboratory, and the department, are headed by Professor Arti Prasad, referred to as a “one-woman army” by her students, who highly respect her leadership and academic qualities. We will also have multiple volunteers undertaking the training, including Professor Neil Lobo from the University of Notre Dame in the United States, Professor Sylvie Manguin from France, several experts from WHO including Dr Eikhan Gasimov, Dr BN Nagpal, Dr Rajpal Yadav, and local experts such as Dr Ranjander Sharma and Mr PT Joshi.

The course will take place from 3 to 5 July 2022 and we will be sharing updates frequently on The Forum page of our Online Resource Exchange Network for Entomology (ORENE) website – a product of the Vector Control Working Group. Watch this space!