By 2030, we will ‘achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls’: these are the words used by global leaders to coin Goal 5 of the Global Goals for Sustainable Development. Today, 8th March 2017, Malaria Consortium is celebrating International Women’s Day together with the global community to show our support for a gender equal world.

Empowering women on a global scale requires a cross-cutting approach, tackling areas that we may not always consider as exerting a direct influence on gender inequality. One issue that has been frequently overlooked as an empowerment mechanism is improvement in global health systems.

The inadequacies of health infrastructure in the world’s most underdeveloped regions has an overwhelmingly and disproportionately high impact on women [1],[2]. Poor or lacking health services lie at the beginning of a long chain of problems contributing to gender inequality.

The absence of health infrastructure reinforces poor health; poor health reinforces poverty; poverty reinforces gender inequality. For example, poor health often causes additional economic pressure on a family which can result in girls being taken out of school, or to women staying home to care for sick children rather than work. It can also lead to lasting disability due to pregnancy and childbirth. These are just some of the ways in which poor health among the poorest and most vulnerable impacts on women in particular, resulting in women being less educated, less economically independent and less empowered than their male counterparts.

And this develops into a cycle, with gender inequality also reinforcing poor health. Women are, in many regions, not permitted responsibility for decision-making and must seek permission to receive healthcare for their children and themselves from their male counterparts. In many regions, where men only allow their female family members to seek treatment from women health workers who may be few and far between, this has serious consequences on women’s health and empowerment.

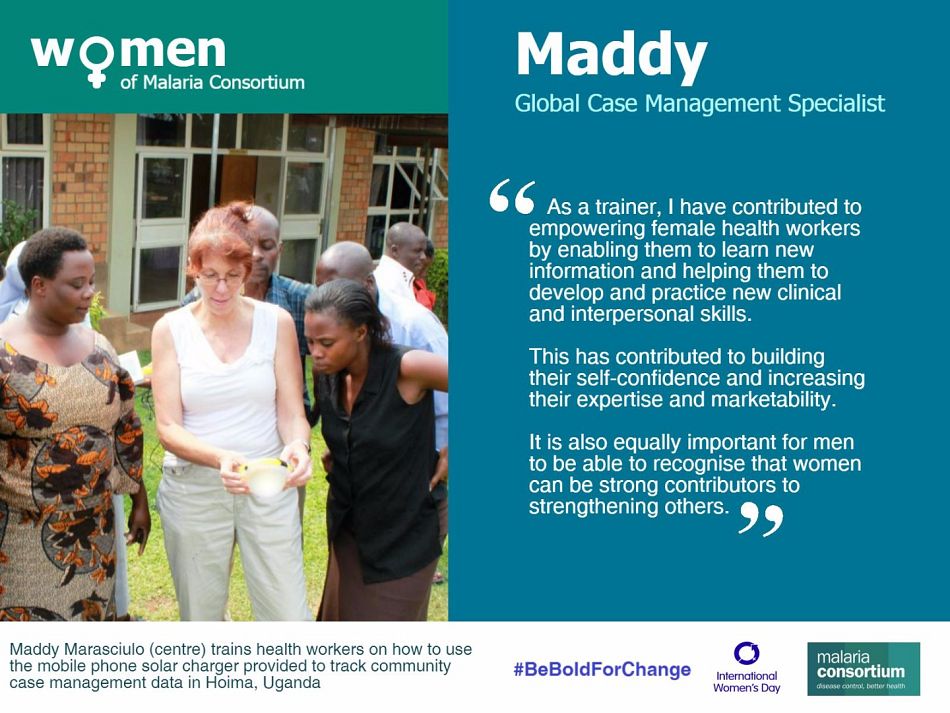

So how has Malaria Consortium worked to combat this gap? In our programmes to tackle malaria and other communicable diseases, we ensure women are both consulted and represented as a critical element of our targeted beneficiaries. One particularly effective intervention that we use is integrated community case management (iCCM) for common childhood illnesses – pneumonia, diarrhoea and malaria, and nutrition. iCCM involves working with and training people within the community to diagnose and treat these diseases, thereby addressing the challenges of access to quality healthcare. Malaria Consortium has supported ministries of health to train and equip community health workers in iCCM in Mozambique, Nigeria, South Sudan, Zambia and Uganda to diagnose and treat or refer sick newborns and severe cases to the nearest health facility. Through iCCM, we also help to raise the social status of women by training female community health workers, a positive step recognised by WHO [3], which also increases access to health services for many more women and their children.

Women make up 69 percent of the community health workers trained through our projects in South Sudan, and around half of our community health workers in Uganda, who are known as ‘true village heroes’ in their communities. Around 30 percent of health workers in Mozambique treating and diagnosing sick children are women, as well as many of our project staff.

By including women health workers in our iCCM training, we have helped to increase significantly their confidence and status among their fellow community members. These women have set an example for their peers. Their work in treating and diagnosing diseases brings life-saving health services closer to people’s homes, freeing mothers from burdens they would otherwise face, such as going to distant health centres, missing out on work, or taking care of sick children.

In recognition of the fact that poverty is one of the primary causes of disease, Malaria Consortium works to bring change to systems that maintain or exacerbate inequality. We are eliminating various barriers to healthcare, including setting up care at community level, involving women in our projects or facilitating access to appropriate healthcare for women at higher level health centres. We bring together all stakeholders, including ministries of health, local leaders and remote communities, to strengthen health systems that are appropriate for the needs of those we aim to serve, so that communities can extract themselves from the cycle of poverty caused by poor health and, in so doing, tackle the associated elements of gender inequality.

As global health priorities falling under Goal 3 of the Global Goals, malaria, communicable diseases and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) cross-cut with Goal 5. Most communicable diseases, NTDs and malaria, are treatable and/or preventable, yet prevail in underdeveloped regions and force economic turmoil on households affected by them. Reducing these diseases is cost-effective and relatively straightforward with sufficient and sustained investment, so Goal 3 should be an easy target to meet, particularly with the support of interventions such as iCCM. This is also highly cost-effective way of empowering women in the long-term.

Certainly, the road to women’s empowerment is more complex than simply reducing disease and providing good healthcare. But it is only with a global understanding of women’s health needs, combined with health infrastructures relevant to their cultural context, that the journey to women’s empowerment will be accelerated.

[1] p.16-17, The global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescent’s health (2016-2030)

[2] p.54, The global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescent’s health (2016-2030)

[3] p.1, WHO guidelines on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes